Re-Making Guernica

In a team with two other researchers/writers/enthusiasts, I have been working on developing the Art-for-Peace Handbook to

work with conflict-affected communities in Ukraine. The idea of the team members - Olesya Geraschenko, Olga Zeleniuk and myself - was to create a

resource that would combine both conceptual grounds and practical activities for

readers with regards to the connections between visual art and peace as well as

the potential of the former to foster the latter. The Handbook is in Ukrainian.

The full version of it will later be available on the website of the Ukrainian

Institute for the Future. Among the exercises I developed is the remake of

Picasso’s Guernica – in the form of a collage. This blog post serves to explain

the significance of the exercise in the discussions and empirical experiences of

visual art-making for peace. The explanation starts with a background on

Picasso’s Guernica, followed by a conceptual discussion on visualizing peace and

visuals enacting peace. Then, I elaborate on the transformations I introduced

into the visual material for the Guernica collage exercise in the Handbook. I

also explain the significance of the collaging technique in terms of ‘the moral

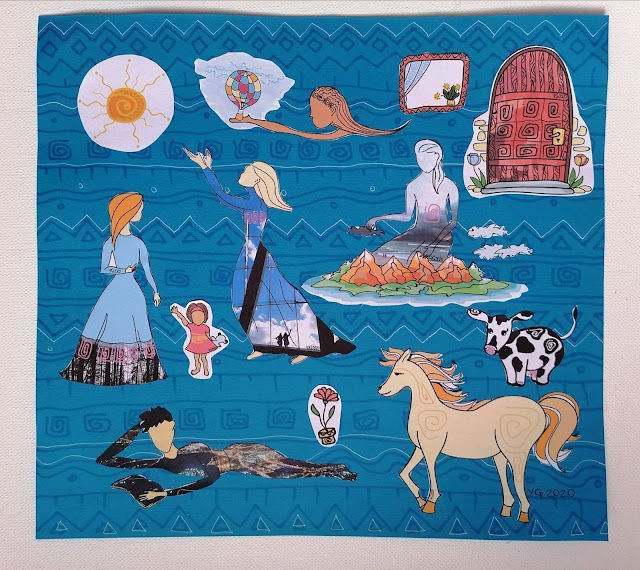

imagination’ needed for peace work. Finally, I present my version of Guernica –

not only ‘against war’, but specifically ‘for peace’.

|

| Final version of the collage by Yelyzaveta Glybchenko |

Background on Guernica

Created in 1937, Picasso’s Guernica is “twentieth century’s most powerful

indictment against war, a painting that still feels intensely relevant today”

(Robinson, n.d., para.1). It was commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion in 1937

Paris World’s Fair. Diverting from the fair’s theme of modern technology,

Picasso created a political piece of art to condemn the intentional killing of

civilians in the 1937 bombing of the Spanish village Guernica. On April 27,

1937, Hitler’s air force supported the fascist forces in the Spanish civil war

by committing the first in history aerial bombing of a civilian population

(Robinson, n.d., para.4).

The anti-war message of Guernica is so strong, that,

when Colin Powell announced the plans of the United States to bomb Irak in 2003,

the artwork behind him – Guernica – was covered. In an opinion piece for The New

York Times, Maureen Dowd wrote: “Mr. Powell can't very well seduce the world

into bombing Iraq surrounded on camera by shrieking and mutilated women, men,

children, bulls and horses” (2003, para.3).

The artwork is “timeless” and

“universally relatable”, as Lynn Robinson notes (n.d., para.12), - in its

message of condemning war. And while Guernica’s significance is indisputable, a

discussion of some concepts and ideas around it would indeed benefit our

understanding of the potential of visual art-making to contribute to peace work.

|

| Reproduction of Guernica on a wall. By Jules Verne Times Two / www.julesvernex2.com, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=85668776 |

Contributing to Peace through Visual Art

Making (visual artistic) statements

‘against war’ is not the same as making those ‘for peace’ – at least with

reference to ‘positive peace’ and ‘quality peace’. Positive peace, as explained

by Johan Galtung (1996), is an inclusive, socially just arrangement which transforms not only direct physical violence, but also the cultural and

structural forms of violence, and implies a presence of mechanisms and tools to

constructively address conflicts. Quality peace, as elaborated by Peter

Wallensteen (2015), possesses such qualities, which would prevent the conflict

from recurring while ensuring dignity, security and predictability. By not

showing elements of peace in Guernica, Picasso references peace through –

precisely – its absence. In this sense, Picasso’s approach resembles that of

photojournalists, who, as Frank Möller notes in Peace Photography, “approach

peace by showing its absence” (2019, p.14).

Later in the same work, Möller

explains that shifting “the discursive focus” from violent conflict to peace is

a “precondition” for the “political move” towards peace (2019, p.26). At the

same time, visions of peace would call for a “focus on process” (Möller, 2019,

p.29) - similarly to how peace itself is a process. In particular, John Paul

Lederach refers to peace as a process by defining it as "a continuously evolving

and developing quality of relationship" (2003, p.24). Would another version of

Guernica, referring to peace in more explicit ways, be more challenging to cover

up when grave decisions are made? Would visual art searching for visions of

peace make us more thoughtful of the content and consequences of our decisions?

Would it contribute to our understanding and actions for peace? According to

Möller, visual art would - along these lines (2020, p.29):

“Searching for images of peace aims at undermining appearances of violence as inevitable or legitimate, an important step in the search for more peaceful social relations in our everyday lives and in world politics.”

This way, depicting peace or its

elements legitimizes aspirations for peace and the search for it, challenging

and altering the definition of peace and how it is enacted (Möller, 2020, p.29).

If visions of peace differ or compete, visualizations of them may contribute to

the process of negotiation of peace-related values until a common ground is

found. If peace is a process, an artistic visualization of it may not

necessarily capture ‘peace’ in the entirety of its collective vision. The nature

of peace as a process implies it is always a work in progress – work on

addressing conflict constructively and using it as a possibility for peaceful

development. This way, elements of conflict may be part of visions of peace.

Important in peace work through visual art is the ability to exercise

imagination – ‘the moral imagination’in particular. Lederach explains the

concept as the ability to recognize opportunities for constructive change and

imagine solutions, which, while rooted in the challenges of today – the

conflict, transcend those realities to create a web of peaceful relations

(2005). Since exercising the moral imagination to create such a web would

require creative oscillation between the conflict realities and the visions of

the future, an artistic activity fostering that would benefit those entering the

path of peace work. That is why the Art-for-Peace Handbook contains two

collages.

The Guernica collage is preceded by a collage activity based on the

project I have been running for four years – Color Up Peace. The project invites

people from all over the world to submit photographs of what peace represents to

them, which I later turn into coloring pages. The idea is to develop and share

visions of peace, foster inter-cultural dialogue and collaboration through

collective mixed-media art-making, break the violence-centered stereotypes of

depicting conflict-affected communities, and allow visual art-making to work for

peace. The Color Up Peace collage activity offers the readers/creators/artists

working with the Handbook to create their vision of peace based on the visual

material provided and those elements they want to add (collaging is not

restrictive in this sense at all). The provided elements are visuals drawn by me

digitally. They depict those elements which often feature in the photo visions of

peace submitted to Color Up Peace. Also available are the words which often are

part of the description/explanation each Color Up Peace participant submits along with

their photo.

Framed this way, collage is a perfect metaphor for the moral

imagination. Rooted in the realities – the visual material provided – the

activity allows for arranging a web of relationships between the elements as

well as adding anything the collage creator would see fit for the vision of

peace. By using the elements from visions of peace, the Color Up Peace collage

takes the exercise to the level of negotiation of peace-related values – at

least metaphorically.

Having so explored the collective and individual visions

of peace, one will move to the Guernica collage. The logic of such transition

reflects my belief that transforming a depiction of war into a vision of peace

requires prior exploration of what peace means – for oneself and for others. The

Guernica collage activity also offers a set of pre-made by me transformed

elements and characters of Picasso’s Guernica. I intended the transformed visual

material to enable the collage creators to make peace visible in their version

of Guernica.

My version of Guernica

The first thing one notices about my version

of Guernica is that it is in color. The color-related decision on my part was

not only driven by the need for brightness and briskness in my understanding of

peace, but also by the arguments of Juha A. Vuori, Xavier T. Guillaume and Rune

S. Andersen. The scholars argued that colors do not only acquire and communicate

meanings, but also “(can be used to) do things in a performative sense” (2020,

p.57). One of those 'things' may be peace work.

Apart from using colors, I also

used photographs to fill in some of the characters’ outlines. The usage of photo

material is another artistic metaphor for moral imagination. I took those photos

which at some points in life represented ‘peace’ to me (in different and

developing understandings of the term), making the characters ‘grounded’ in the

realities. At the same time, each character transforms the photograph

transcending the realities it is rooted in – a process, which is further

reinforced through the nature of collaging. And the characters’ outlines limit

what is visible and what is not visible out of the photo. I took the photos

myself in Tampere, Finland; Cape Town, South Africa; Oslo, Norway; and above

Dubai, the United Arab Emirates. I selected the photos not based on the

geographical location of the visualized, but based on what is depicted.

I

transformed the characters and elements of Guernica the following way:

1. The

lamp in the form of an eye turns into the sun – to highlight how natural peace

is.

2. The dead soldier is now alive, and he is reading a book – to emphasize

the importance of culture and education in establishing peaceful relations. The

flower growing out of the broken sword in the hand of the dead soldier is now a

well-growing potted plant.

3. The mother is now stretching her hand to take her

alive child’s hand, which is a reference to inner peace and harmony in immediate

social circles like the family.

4. The cow and the horse now look healthy and

well – to stress the importance of the environment and animal rights for peace.

5. The woman who enters the scene through the window is now holding a hot air

balloon in her hand – a symbol for the moral imagination and creativity in peace

work.

6. The woman who was originally in flames is turned into a symbol of

nature, situated in the mountains on the ocean, - another way to highlight the

role that the environment and natural resources play in peace and conflict.

7.

The woman who previously dragged her hands behind her in despair is now

gracefully stretching her arms towards the sun. Her movements look natural.

8.

The door and the window are designed to convey the atmosphere of a

well-looked-after home.

I on purpose did not draw the faces of the characters to

allow those working with the Handbook to imbue those emotions into the piece, which

they find appropriate. The facial expressions are also a way to create new

connections between the characters and elements of the piece. Showing the relationships between the characters and the elements of this version of Guernica also fosters the process of the moral imagination. Like this, the collaging artist would practice developing a web of peaceful relations on the canvas.

The final result of my own attempt at creating a new Guernica for peace can be seen above in this blog post. Below, you can see

the video reflecting my collaging experience:

I would be very interested to hear or read the thoughts and impressions of the readers!

Bibliography

Dowd, M. (2003). Powell Without Picasso, The New York Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/05/opinion/powell-without-picasso.html

Lederach,

J. (2003). The little book of conflict transformation. Pennsylvania: Good Books

Intercourse.

Lederach, J. P., & ebrary, I. (2005). The moral imagination: The

art and soul of building peace. New York;Oxford;: Oxford University Press.

Möller, F. (2019). Peace Photography. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03222-7

Möller, F. (2020). Peace aesthetics: A patchwork. Peace & Change, 45(1), 28-54.

doi:10.1111/pech.12385

Robinson, L. (n.d.). Picasso, Guernica, Khan Academy.

Retrieved from:

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/cubism-early-abstraction/cubism/a/picasso-guernica Vuori, J., Guillaume, X., & Andersen, R. (2020). Making peace visible: Colors in

visual peace research. Peace and Change, 45(1), 55–77.

https://doi.org/10.1111/pech.12387

Your version of Guernica - for peace - is spectacular! You are incredibly intuitive and creative, Yelyzaveta. The way you interpret, reimagine and transform. The integration of colour and your own photographs (and visions of peace) is ingenious. I understand that the collaborative Art-for-Peace Handbook is being developed to work with afflicted Ukrainian communities, but will it perhaps be available in English?

ReplyDeleteThank you so much, Shehaam! I always value any kind of feedback on my art work and this blog. This instance of receiving feedback is especially heart-warming. Indeed, my colleagues and I intend for the Handbook to be in Ukrainian since we are developing it to work in the context of Ukraine. However, I will translate into English the exercises I created - and I will make them available online. When that happens, I will come back to your comment and let you know!

Delete